St Mary of Eton, Hackney Wick

The Story in Depth

The Victorian Grade II listed church was in a state of disrepair and the parish had no funds for the extensive works. In a part of London with high housing need, what would they do?

-

Starting point

In the early 2000s, St Mary of Eton’s grade II* listed church was falling apart: the roof was partially missing, all the lead guttering had been stolen, water was coming into the nave, the vicarage was crumbling, and the small congregation was struggling financially. The PCC approached Matthew Lloyd Architects (who had previously worked on St Paul’s Old Ford nearby) to envision an effective way of using the land that would also provide financial relief to the church.

-

The plan

The goal was to redevelop the site by providing affordable housing and release value which would be used to rescue the church from decay. This would restore the church building for worship and community use, and make a much-needed contribution to meeting local housing need. Matthew Lloyd’s vision was to design the new housing to correspond with the Victorian architecture of the church.

-

The journey

The PCC used their reserves to gain planning and listed building consent independently, granted in 2011 and varied in 2012. The consent allowed for demolition of the severely deteriorating old church hall, making way for conversion and refurbishment of the site into two residential buildings (with a mix of one-, two-, three-, and four-bedroom flats) and one ground floor commercial unit.

The original intention was to provide social housing on the site, but this did not end up being possible. The PCC initially worked with a housing association, but they failed to come up with a viable solution and did not have sufficient drive and determination to find a way through a difficult project, and so they dropped out.

The PCC reluctantly compromised but nevertheless progressed the project, coming to an agreement with Thornsett Living Limited, who had a track record of working with church land. The Church leased the land to Thornsett in November 2012 for a period of 149 years but retained the freehold.

Hackney Borough Council agreed to waive the requirement to include social housing on the site on the basis that value was going back into the church building and that the new facilities would benefit the community.

Matthew Lloyd Architects worked creatively with the small space and incorporated the views of the local community through planning consultations. The result was 26 apartments in three buildings and a new vicarage positioned around a central courtyard, plus a completely new church hall for use by the community. The project incorporated a green roof and photovoltaic cell panels generating the power to light the building. While the works went on the congregation worshipped in a nearby church.

The project was completed and apartments went on sale in 2014: a local sales policy ensured that tenants were local to Hackney Wick. The flats occupied by purchasers or rented out; however, the rents were only affordable to people on high salaries – for example, a 3-bedroom apartment was let at £3,200 pcm.

The commercial unit was leased initially to a dental practice and is currently a shop.

-

Resources

The PCC used their existing reserves to fund the planning consent process, which gave them control over the development and choice of partner. The sale of the leasehold to Thornsett then gave the church the financial boost it needed.

The development cost £7 million and incurred a CIL contribution of £43,225. The planning agreement also required a commitment that £700,000 from the sale of the flats would be reinvested in the refurbishment of the listed building.

-

Keys to success and biggest challenges

The project was characterised by bravery and boldness: from the PCC, who put their financial reserves into saving the church building; from Matthew Lloyd, who strikingly reimagined the church’s surroundings; and from Thornsett, who were willing to take on a difficult build in a physically tight space as economically as possible. The project received planning consent despite involving a listed building, and English Heritage were helpful and co-operative.

Thornsett carried out the much-needed external repairs to the church as part of the project, but left without fully making good. One wall in the church is still unpainted to this day, and the church’s energy meter is inconveniently located inside one of the new apartment buildings.

The biggest challenge however, which the PCC could not overcome, was trying to deliver affordable homes without the project becoming unviable.

-

Final outcomes

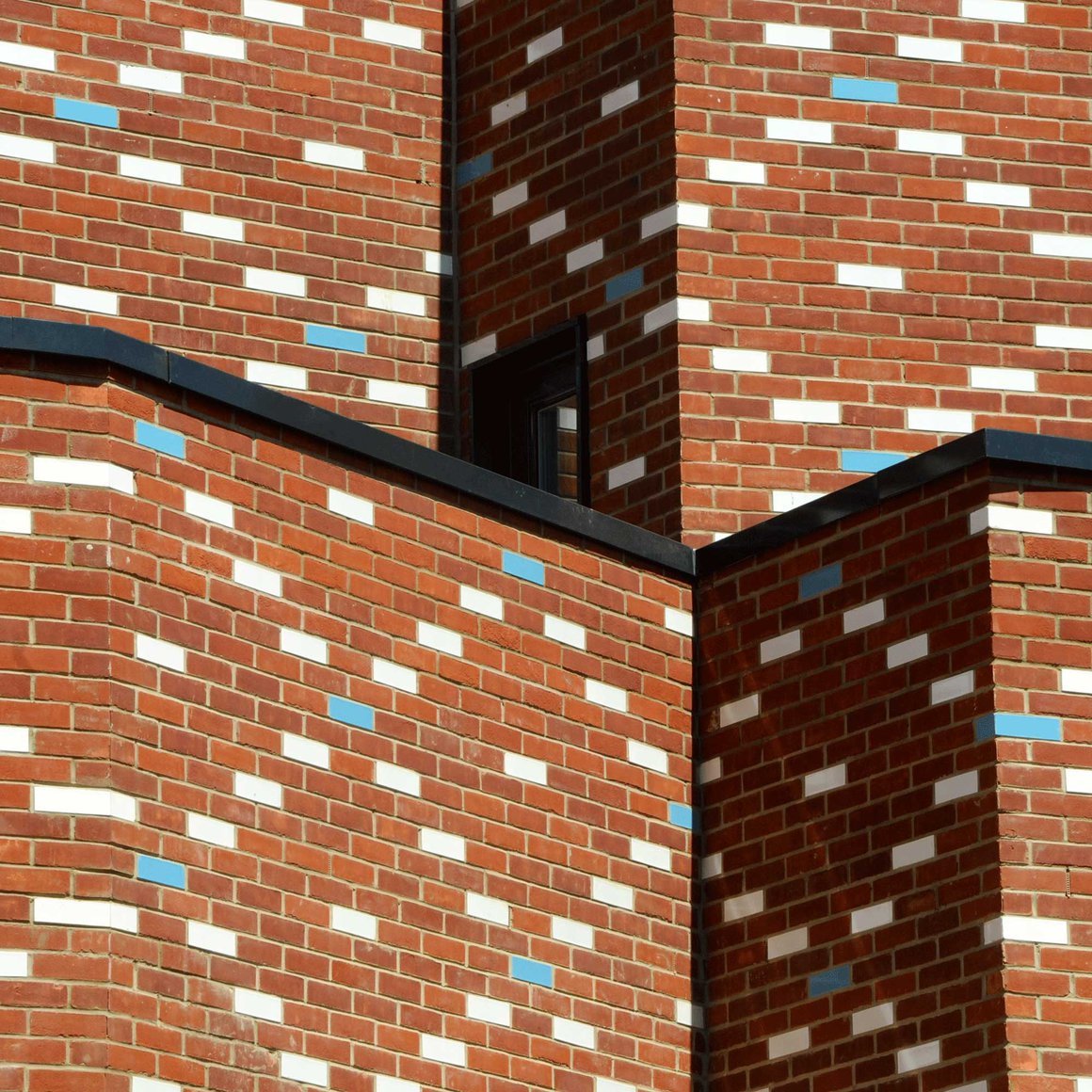

The development generated funding for a church approaching irreparable deterioration. Thornsett lists ‘land payment and sustainable income sources (ground rent and rental income)’ as the top benefit to the client for this project. The new church hall is a hub for the community. The complex has become a striking feature of the area, with architecture that won RIBA awards in 2015. The project provided an active and revitalised church for a sustainable congregation.

On the other hand, the fact that the PCC had to put aside their original desire to create social or affordable housing in the face of financial constraints demonstrates the challenge of using church land in a way that fully aligns with mission.

-

Photo credits Matthew Lloyd Architects and sludgegulper cc-by-sa-2.0

For further information on this case study, contact The Church Land Trust on theclt2021@gmail.com.

The site prior to redevelopment

Steel frame being erected for one of the new apartment blocks

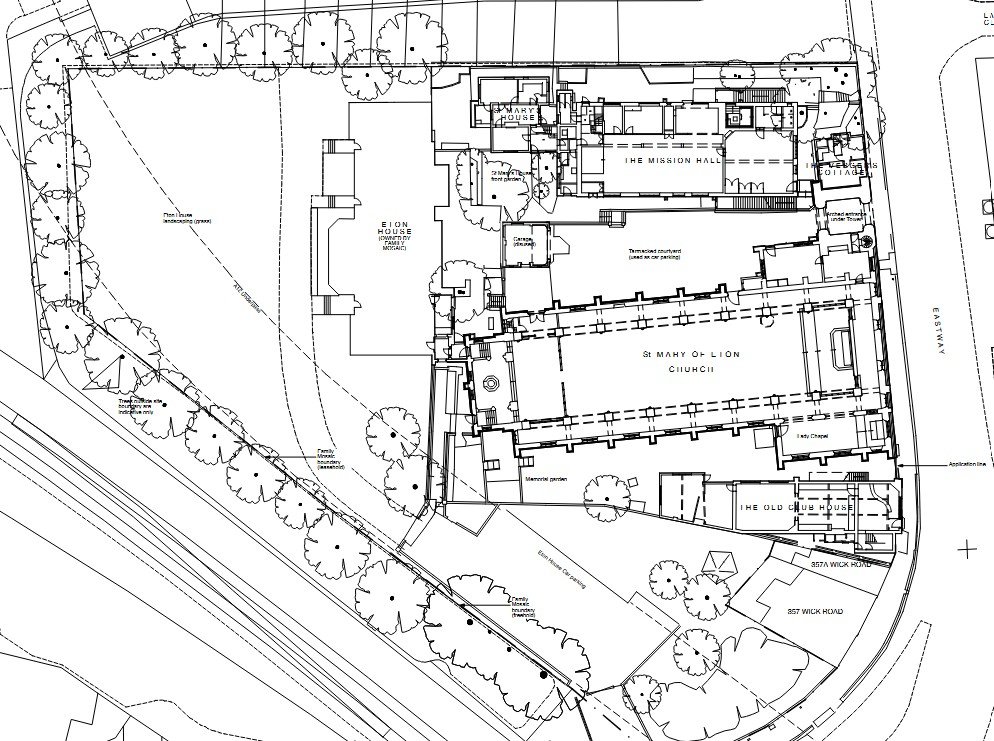

Plan of the original site

Architect's plans for the redevelopment

New street view

View from the new interior courtyard

Repaired and refurbished interior

Striking design elements from Matthew Lloyd Architects